Guest blog by Eric DeLuca: Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning Manager at Translators without Borders

Obtaining accurate data is fundamental to correctly assessing the needs of internally displaced people (IDPs). Effective communication with the people you are serving is fundamental to that process.

Yet too often aid organisations and other service providers lack information on IDPs’ primary languages and literacy rates to know which languages and formats to use to communicate with them.

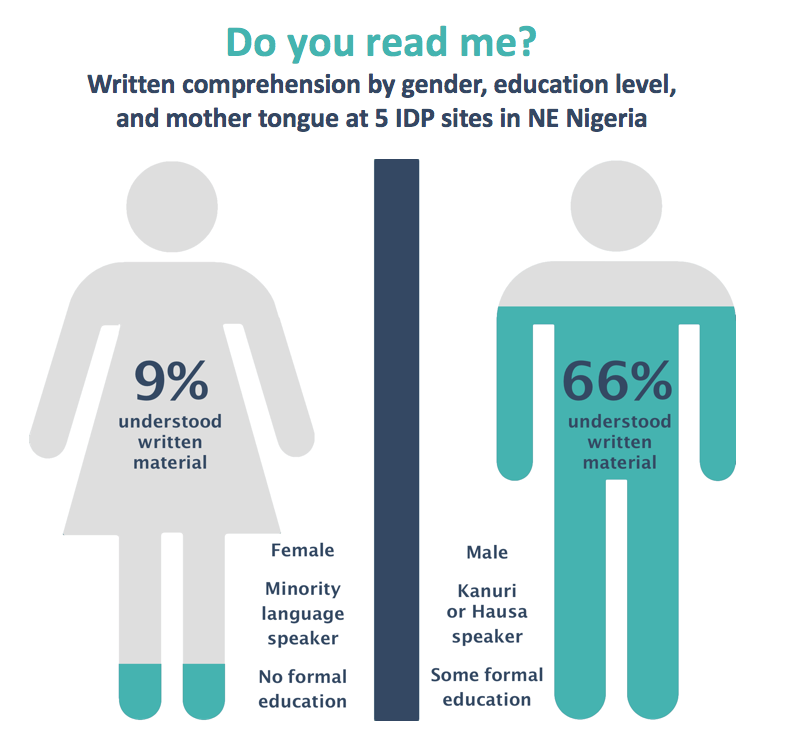

As highlighted in the Methodological Annex to IDMC’s 2018 Global Report on Internal Displacement, north-east Nigeria, where more than 70 languages are spoken, provides a striking example. I visited Borno State in May 2018 for Translators without Borders, and personally witnessed this problem.

There are three major issues with data on IDPs’ languages in north-east Nigeria, and broadly in humanitarian emergencies around the world.

- We lack an authoritative, verifiable and regularly updated data-set for languages globally. Census data is often years old and requires correlation with information on IDPs’ places of origin. The only data-sets that exist are proprietary, expensive, static and outdated.

- Aid organisations do not routinely collect data on the languages of IDPs or other people affected by emergencies – and when they do, they rarely share it.

- We don’t routinely address language issues when collecting data.

I saw this last problem first-hand in Maiduguri when I conducted a workshop with a group of 24 people who regularly conduct surveys for aid organisations. Over 90 per cent felt that language was a serious barrier in their work.

These data collectors are expected to sight-translate English-language surveys into their mother tongue (Hausa or Kanuri), and translate the responses back into English to complete the form. When the respondent speaks one of the other 30 - 40 languages regularly reported as IDPs’ mother tongues, a third party is asked to interpret. This will typically be another IDP or a member of the host community – not a language professional, not trained in interpreting, and probably not an expert in the subject matter. Sometimes nobody has the right language skills and the interview relies on ‘a combination of very basic Hausa and body language’ or the respondent is skipped.

So either the minority language speaker is not heard, or what they have to say is filtered through multiple translations: English to Hausa to, say, Marghi and back again - the potential for information to be lost in translation is huge.

If data collectors don’t properly understand the English terms used, or know how to translate them into other languages, the information loss is even greater. We tested the 24 data collectors’ comprehension of ten of the English terms commonly used in their surveys. On average, they understood only 35 per cent of the words tested. The scores improved with experience, but even those who had been running surveys for over six months still understood less than half of the selected terms. Commonly used acronyms were particularly problematic.

If data collectors don’t properly understand the English terms used, or know how to translate them into other languages, the information loss is even greater. We tested the 24 data collectors’ comprehension of ten of the English terms commonly used in their surveys. On average, they understood only 35 per cent of the words tested. The scores improved with experience, but even those who had been running surveys for over six months still understood less than half of the selected terms. Commonly used acronyms were particularly problematic.

We know this has an impact. Surveys inform our collective assessment of need. We spend time labouring over the exact wording of questions to reduce bias and ensure accuracy. Yet we rarely analyse the language dynamics of our data collection process, or systematically check that data collectors communicate questions accurately. If we are hearing from some groups and not others, or if information is garbled through mistranslation, then organisations serving IDPs do not have a good basis for decision-making. Individuals who are unable to communicate their needs directly in English or Hausa may not get the support they need.

These are not insoluble problems. All three challenges above can be readily addressed to improve humanitarian data on the needs of IDPs and host communities, in north-east Nigeria and globally.

Solution one: Build an open-access language data map – Translators without Borders is working on this with colleagues from the research sector. Please get in touch if you’d like to be part of it or just to know more.

Solution two: Routinely assess the languages and communication needs of affected people – A handful of standard questions added to every household needs assessment survey would map the affected population of each humanitarian emergency in a matter of weeks.

Solution three: Support data collectors with language and terminology – Ideally a survey should be translated into the language in which it will be conducted. This allows survey data and responses to be gathered more reliably. When that is not feasible, language-specific training and terminology support can prepare survey leads to relay questions accurately. Avoiding technical jargon and acronyms can improve the reliability of survey data and ensure interviewees’ voices are heard. Finally, data collectors should speak the language of the respondent, or at least be able to call on trained interpreting support.

Be part of the solution -- This is how we understand and respond more effectively to the needs of IDPs.