IDP settlement in Baido, South Central Somalia.

Photo: NRC/Nashon Tado

In March, the journal Nature published a special edition on human migration (volume 543 number 7644 pp.152-280), which does an excellent job of synthesising a lot of information and research on the study of human mobility and the increased use of technology to monitor the phenomenon. It takes stock of the existing situation and analyses it from different perspectives. In short, it’s a must read.

The issue’s editorial is entitled “Data on movements of refugees and migrants are flawed” (you can guess what it’s about). A second article entitled “What the numbers say about refugees” argues that those shaping the discourse on migrants and refugees are not using the available evidence responsibly. Instead, they (mis)use it to stir up fear of an “invasion”. “Migration tracking is a mess”, by Huub Dijstelbloem, reviews methods for monitoring human mobility and hit close to home given our role as the global monitor of internal displacement.

From our perspective, Nature couldn’t have timed the publication of this issue better. It came just as we started meeting to finalise (or “lock down”, as we say) our year-end estimates and figures ahead of our annual Global Report on Internal Displacement (GRID). Up to our necks in data, we read the issue with great interest and recognised the challenges raised. Compiling global figures on internal displacement, refugee statistics or international migration is a maddening, humbling experience. Attempting to do so requires us to resolve a number of issues including:

- spatial and temporal data gaps

- differing definitions of the same phenomena

- inconsistently labelled data

- how to accommodate data from a variety of source types

- different reporting units (650 displaced families equals how many displaced people?)

- mismatching geographical boundaries

- scant metadata

- unexplained changes in data providers’ methodologies

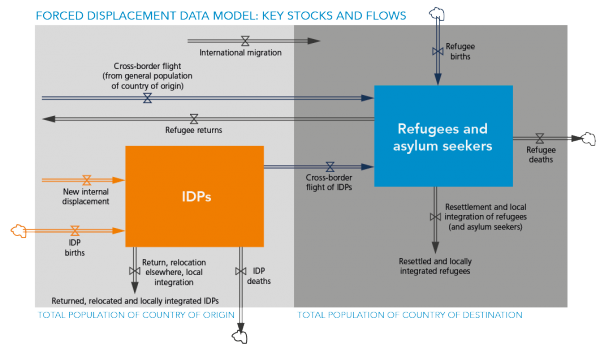

In many cases there isn’t even direct observational data on the phenomenon in question, be it new displacement, returns of internally displaced people (IDPs) or their onward flight across borders, leaving us to infer what’s happening indirectly from other data points. If internal and cross-border displacement were simple and unidirectional processes with a single cause, these gaps would not pose such a problem, but given the many factors that explain why a number goes up or down, missing that disaggregated data and contextual information keeps us awake at night and constantly on the phone and Skype with our colleagues in the field.

What to do?

We’ve all heard plenty of calls for “more and better” data, but that is not specific enough to be actionable. We also agree that new kinds of data and means of analysis are needed to track displacement and migration, and we are piloting several methods right now. More information on our #IDETECT challenge is available here. In addition to technological solutions, there are several concrete steps that can be taken to improve the quality and interoperability of data and ensure it is used more responsibly by policymakers, the media and others.

1 - Common standards, terms and definitions

Data on IDPs, refugees and migrants is collected by a wide range of institutions for numerous reasons, and measuring flows is not always the purpose. Each institution has its own mandate and turf wars to fight. The result? Data that is difficult to interpret and nearly impossible to join up. What is needed is a common data model that accounts for all of the relevant flows, a standard set of definitions that applies to each flow or process and - most importantly - technical and methodological guidance to ensure that data is collected in accordance with these standards.

2 - More transparency

Declan Butler’s article rehearses the claim that data on internal displacement is “unreliable”, and to a significant extent we agree. This is why we publish a confidence assessment for our figures on displacement associated with conflict. We feel that even this is insufficient, so we also publish the analyses that lead to our figures for those who want even more information about how we interpret our sources and use their information to generate our estimates.

We publish our information in a spirit of modesty - we wish our numbers were more certain - but the feedback we receive from our partners has been universally positive. Rather than be embarrassed about the shortcomings of our data sets, let’s be more transparent so that we can identify problems and address them together.

3 - More money, less politics

We recently asked one of our data providers why their most recent collection exercise covered a smaller geographical area than previously. They said it was all they could afford at the time. Had we not known that, we might have thought there were fewer IDPs than in the past because of changes on the ground. Instead, it was just a change in measurement brought about by limited resources.

Another country, another problem. The government concerned only allowed our partner to collect data in certain places, and these did not include the area where they knew most IDPs were sheltering. Some governments don’t like to have IDPs on their books, so either they do not allow data to be collected at all, they allow it but only for a short time or in certain places, or they simply declare - without much in the way of supporting evidence - that all IDPs have returned or been resettled.

This is not good enough. Governments at all levels should recognise that having and reporting information on the number of IDPs, refugees and migrants they are hosting is in their own interests. Only when information is gathered consistently and shared openly can we work together to help displaced people integrate into their host communities, return to their homes or otherwise get back on their feet after a conflict or disaster.